Citizenship in Sound

by Kobby Ankomah Graham

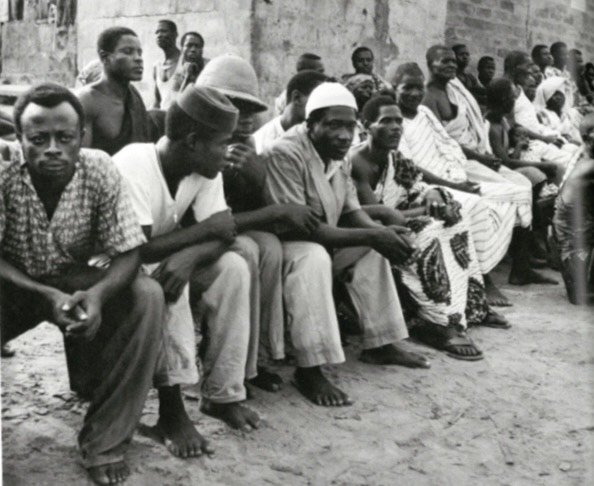

Photographer: Paul Strand

Citizenship as Weight

A roadside bar in the middle of Osu. The sun has just set, and the air is thick with heat and expectation.

A DJ – the first of many - plugs in his decks, and cues a beat that no one recognises, but everyone understands. A girl with green braids smiles at a boy with painted nails. Bodies move in unison. Residents mingle with visitors and, for a few hours, all borders dissolve. This is not escape.

It is nation-building.

In Accra’s alternative communities, young people from different cultures and backgrounds come together to build belonging without asking for passports. Drawn together by sound. Staying for each other. Crowds become temporary nations, bound not by blood or law, but by shared movement. Artists who might have once been confined by ethnicity or colonial borders now find their people through basslines and BPMs:

Citizens of sound.

For many Africans, citizenship is not just legal identity but emotional terrain. A thing that carries weight. The weight of borders drawn by hands that never set foot on soil they divided. The weight of young nations forced to stitch people together from the threads of different tribes. The weight of identity documents that feel more like burdens than they do keys.

To be an African citizen is to be a member of nations barely a century old, yet rooted in identities that predate the modern state by millennia. For our youth, the idea of the nation feels both intimate and abstract: present in passports and constitutions, yet distant from daily textures of care, belonging, and recognition.

In Ghana, the state emerged from the merging of several ethnicities, languages, and histories that had previously related to each other in complex, sometimes contentious, ways. The nation-state was supposed to be the new village; the site of our shared aspirations. All too often however, it has been the administrator of our disappointment.

But diverse as we are and long before we became a thing called Ghana, something already bound us. Something older. Something deeper. A knowing that preceded any map. Here, the Akan called it Nkabom. Elsewhere it had other names, like Ubuntu in the South of the continent, or Ujamaa and Harambee in the East. Different names, same principle. Some describe it as, I am because we are but it would more accurately be described as, I am only a person in relation to others. These were not mere philosophical abstractions; they were daily practices of mutual aid and collective identity, offering frameworks for understanding the self as deeply interdependent; a notion often forgotten in today’s dog-eat-dog world.

Early Pan-Africanist leaders attempted to scale up these communal ethics into national ideologies; a dream that governance could echo the intimacy of village life. Our grandparents speak of the can-do spirit of independence, now immortalized in songs like Ghana Freedom by the legendary ET Mensah and the Tempos. We had just brought imperialism to its knees and thought we could do anything. Nyerere envisioned ujamaa not just as an economic force but as a moral one. Nkrumah spoke of our communal past and a “new African personality.” Of states built not only on sovereignty but on solidarity.

But the machinery of colonial bureaucracy, the weight of the Cold War, and the economic violence of structural adjustment reduced these dreams to little more than that: dreams. Citizenship became legality: possession of an ID; the ability to perform a national anthem; or vote in an election. Those deeper emotional bonds - rooted in care, co-dependence, and cultural continuity – became hard to sustain. The old ways seemed to fade.

Another Way

But maybe these ideas didn’t die. Maybe they just moved. I see their echoes. The things I am most drawn to as a DJ and as a researcher are not to be found in parliament reports and research documents. They are on dancefloors; in living rooms turned into studios; at warehouse parties; and roadside sessions. In clubs, courtyards, abandoned factories, and grassy patches. These spaces, often dismissed, are in fact where politics are being reimagined; where young Africans experiment with new ways of communing and belonging that kick against validation from wider society. The alternative music spaces I see here in Accra embody a citizenship that seems to extend beyond nationality and ethnic group; redefining what it means to belong in a continent where the nation-state is still a fragile idea.

Without knowing it, our young are drawing on ancient philosophies of communalism. These ideals – while difficult to sustain at the level of the State - thrive in spaces that remain largely invisible to government. In such music communities, young people are building something remarkable. Not perfect, but real: a model of citizenship rooted in mutual obligation, and shared rhythm and responsibility.

In Accra, the alternative music scene is a constellation of overlapping communities. From alté spots like Palm Moments and Ria Boss’s Open Mic; womxn-friendly gatherings like Afrodite & Friends and Cultpop Worldwide; to underground electronic raves at places like South Village. These are all spaces where people come together not just to escape, but to build. What draws them is not only sound, but the possibility of seeing and being seen differently.

In these spaces, national identity is irrelevant. A queer dancer from Accra can find solidarity with a producer from Abidjan. A spoken word poet from Labadi shares a stage with an artist from Lagos. Boundaries blur. Accents collide. New language emerges. Organic expressions of philosophies our states have forgotten. Organisers take time to ensure events are safe spaces. Artists pool resources to fund a friend’s video shoot. A group of strangers form a circle to shield someone on the dancefloor. These are not acts of charity. They are acts of recognition. Imperfect spaces reminding us that community can survive where the State fails.

We Are a Rhythm Nation

Music has always held political potential in Africa, but in today’s alternative scenes, it is doing something more. It is not simply reflecting the politics of the day. It is enacting a different kind of polity, where citizenship is defined not by nationality but by participation. You belong because you show up and do the work. You contribute. You listen.

These are often the only places where certain people feel seen. Women otherwise forced to navigate the gendered politics of both public and private life take centre stage. Neurodivergent creatives, often misunderstood in our rigid educational systems, find respect and room to thrive. Queer Ghanaians, increasingly criminalised or culturally marginalised, find acceptance here.

The contrast with state-driven citizenship is stark. Where the state often categorises and polices, these communities include and protect. Where the nation demands loyalty despite delivering little in return, these scenes offer love. Not sentimental love, but the kind forged in practice: in showing up and carrying each other through joy and pain alike. Belonging is shown in the warmth of a hug after a set. In the way a mic is passed to someone new. In dancing for a friend as they graduate from playlist curator to full DJ. In these moments, we practice things our ancestors once lived. Listening becomes governance, and holding space, a kind of leadership. No long talk. Rhythm replaces rhetoric, BPMs become the building blocks of shared experience, and the crowd becomes a temporary nation.

But it goes beyond just music. Language too serves as a vessel for cultural expression and community building. In Ghana, Pidgin has evolved beyond its colonial roots, becoming a dynamic medium through which youth articulate their identities and experiences. In recent years, the absorption of Nigerian Pidgin expressions - fuelled by the proliferation of Nollywood films, Nigerian music, and social media - has further shaped Ghanaian Pidgin. Words like japa - describing escape from difficult circumstances through emigrating - are now common in Ghanaian parlance, particularly among younger generations navigating the kind of economic uncertainty that mirrors that faced by their parent’s generation in the ‘70s and 80s.

This linguistic interplay mirrors the collaborative spirit within Ghana’s alté(rnative) music scene. Artists like Obed of SuperJazzClub and Nigeria’s Yinka Bernie have found kinship and creative exchange across borders. Ria Boss has extended platforms to artists such as Lady Donli, just as Odunsi the Engine did for Amaarae during her early days, including a performance at Art X Lagos in 2018. These are not isolated gestures; they reflect a broader ethic of regional solidarity. Ghanaian rapper M.anifest’s collaborations with alté(rnative) Kenyan artists like Blinky Bill and Karun further reinforce the sense that a new Pan-African cultural movement is being shaped by those working between – and not within - official structures. These relationships are creating more than just new sounds. They are producing new civic and emotional geographies, where artistic kinship models a kind of belonging untethered from the borders drawn on maps.

This is something music has long done, almost everywhere in the world. Think of how Jamaican soundsystem culture helped birth hip-hop in the Bronx, or how jazz, once derided as the music of American vice, became a global symbol of sophistication and freedom. Music has a way of carrying ideas across space and time, connecting those who might never meet, but feel the same pulse. Nkrumah understood this well. For him, music was not just a soft power tool for cultural diplomacy. It was a key instrument of nation building. People need things in common. Music had always served that purpose in our towns and villages. In the aftermath of colonial rule, it could help knit the fragments of our newly imagined nations into something cohesive, something shared.

What’s often forgotten is that the sounds we now call national once came from the margins. The alté(rnative) artists celebrated today are part of a long tradition of fringe cultures that eventually shape the centre. Hiplife is a case in point. Under the Fourth Republic, as press freedom expanded and media plurality grew, a new generation of musicians began crafting songs that drew from American hip-hop and local rhythms alike. Elders often criticised the genre for being too crass or too American, failing to remember that they too had once revelled in the diasporic echoes embedded in early highlife records. The truth is that even around independence, highlife itself was still relatively new. It was the music of youth, shaped by local osibisaba rhythms, danceband brass, jazz imports, and rumblings of calypso. Out of all these borrowed and imposed elements, Ghanaian youth created something distinct and alive. Today’s alté(rnative) spaces follow that same instinct. Borrowing freely and bending borders, they give form to new ways of being together. And like those before them, they remind us that nationhood is never fixed. It is always being played, remixed, and remade.

What our Elders Can Learn

Africa is the youngest continent in the world, its median age hovering around nineteen. This demographic reality is often presented as a problem or a promise. But what if it is a practice? What if the future of the African state depends not on managing youth, but on learning from them? If our governments hope to build lasting nations, they must empower the generation that will inherit them. They must learn that citizenship is more than legal status: it is how people are made to feel they belong.

Music is more important than many of our elders remember. Culture is not static or some snapshot of the past: it is dynamic and ever-evolving, and you can see this in music. Slice open its different decades and sonic descendants - palm wine, big band, Ghana funk, burger highlife, hiplife, azonto, afrobeats - and you can trace the entire history of modern Ghana in highlife. If you think about it, it is wild that we do not have a museum dedicated to it: it would tell you everything you need to know about Ghana.

The Fourth Republic is the only Ghana many young Ghanaians have ever known. Whether born in 1992 or in the years that followed, they have grown up in the shadow of democracy; familiar not with coups or curfews, but with campaign promises and ballot boxes. They’ve watched up to six presidents come and go, and seen power shift peacefully between parties at least four times. The turmoil that scarred the ’70s and ’80s - the dusk-to-dawn curfews and clampdowns that drove artists abroad or into the arms of the church - belongs to history books.

If African states are serious about building inclusive futures, they must pay attention to the blueprints already unfolding beneath their gaze. Not just in conferences or policy briefs, but in its cultural spaces, whatsapp groups, and bedroom studios. The alté(rnative) music scene is not just a cultural fringe: it is a civic laboratory.

Here, people practise what the nation preaches but rarely performs: inclusivity, mutual responsibility, freedom of expression. And they do so with limited resources, often in the face of censorship, neglect, or moral panic. What would it look like if states supported rather than surveilled these communities? If funding flowed toward subcultural creatives and collectives, and not just commercial acts? If policy treated culture not as entertainment, but as civic infrastructure? I am not arguing that underground scenes should be co-opted by the state. Their power lies, in part, in their independence. But there is room for respect, for protection, for recognition. The state could learn from their ethic of care, and emphasis on participation over hierarchy.

Most of all, the state could learn that citizenship is not a status to be bestowed, but a practice to be lived. In these alté(rnative) spaces, I’ve seen a kind of citizenship that is lighter, freer, more humane. A citizenship where no one is illegal, and everyone has a verse.

Imagine if citizenship was taught not just through civics, but through curation. Through collaboration. Through care. Imagine a Ghanaian state that embraced the ethics of its subcultures. A government that invested in cultural spaces not just as entertainment, but as infrastructure. A nation that treated DJs as cultural archivists, studios as classrooms, and dancefloors as town halls.

The alternative scenes I describe are not perfect, but they could be instructive. They demonstrate that inclusion is possible. That communalism is not a memory, but a method. What we are building in these spaces is not a rejection of nationhood. It is a reimagining. A way to remember that the most radical act can be making each other feel at home instead of the othering that often happens between Ghanaians despite living in the same borders. Here, a song can be a passport, a beat can be a border crossing, and care can be a constitution.

Though difficult, the lesson is simple: start from where people are, build from what they know, and – most importantly - honour who they are becoming. Recognise that sometimes the most powerful forms of nation-building are not led by presidents or parliaments, but by people with purpose and - maybe - playlists.

As the continent moves into the 21st century - with climate crises, economic uncertainties, and shifting geopolitics - the need for resilient, inclusive, and imaginative citizenship will only grow. Maybe the answers won’t always lie in textbooks or treaties, but in the basslines of Africa’s many sounds. In the quiet generosity of communities carrying each other’s burdens. In the drum patterns of tracks that make strangers dance in togetherness, and nobody is left behind.

Music need not be relegated to the background of our lives. Maybe it can be a blueprint too.

***

About Kobby Ankomah Graham

Culture Geek. Writer. DJ. Academic-in-Denial.

London made me. Cape Coast raised me.

Reimagining Ghana means listening to the youth upon whom reimagination will inevitably fall.