1957 Fragments of a Potter’s Portrait.

by Kofi Dzogbewu

Photographer: Paul Strand

PART 1

A.

There is a surge of something unmistakable – courage, defiance, loyalty, and a fierce pride – that floods the spirit whenever one listens to Dr. Kwame Nkrumah’s declaration of Ghana’s independence on the night of

March 6, 1957.

His voice, steady and unrelenting, still echoes across time, awakening dormant convictions in the hearts of listeners. I remember, as a child in class six, pausing to listen to a replay of that historic speech on the radio during an Independence Day celebration. Turning to a friend, I said with unshakable certainty: “As long as Nkrumah’s speech is played whenever we are on the edge of despair, no leader – foreign or local – will ever succeed in oppressing Ghanaians.”

To me, and to many others, that speech was more than a historical artifact. It was a shield. A spell. A reminder that we had once broken free, and that we could do so again. It lives in our collective consciousness not just as a national memory, but as a recurring rallying cry – summoning us, time and again, to remember who we are, what we have overcome, and what we are still capable of resisting.

Ghana is more than a geopolitical entity. It is a living idea, drawn from the deep ancestral wells of West African history. Though the modern nation shares no borders with the ancient Ghana Empire, its very name is a conscious reclamation, a symbolic alignment with a legacy of wealth, intellectual advancement, and sophisticated statecraft (1). When Ghana chose its name at independence, it merely historical nostalgia; it was a political and cultural statement, positioning Ghana as the inheritor of a pan-African heritage rooted in dignity, self-determination, and intellectual achievement. This act of naming became prophecy in 1957, when Ghana emerged as the first sub-Saharan African country to break free from European colonial rule. Led by Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana's independence reverberated across the continent and the globe (3). It wasn’t just political liberation; it was a psychological and cultural revolution. Ghana refused to inherit the silence of oppression—it spoke, and in doing so, gave voice to millions. It became the proof that freedom was not only possible but inevitable.

Ghana is an idea—an enduring concept born of ancient greatness, resisting oppression and constantly reaching toward liberation.

Though its post-independence journey has been riddled with contradictions—economic struggles, political instability, and social fragmentation—Ghana continues to return to the pulse of its founding vision: a people rooted in collective agency and cultural pride. Through language, festivals, oral traditions, and a fierce protest spirit, Ghanaians resist the pressures of global homogenization (4). Despite silencing attempts by the powerful, the people still march, speak, strike, and demand.

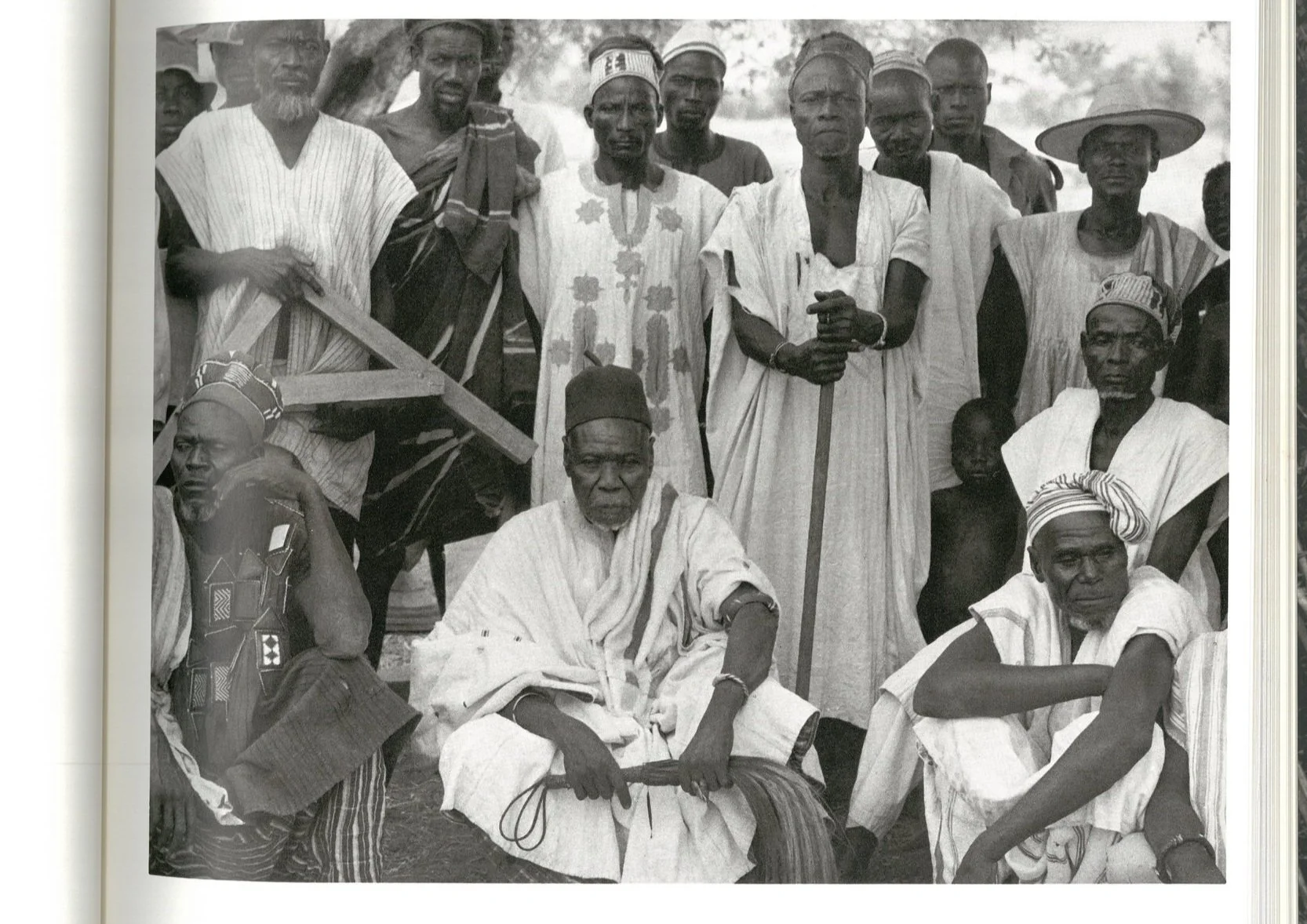

This spirit of resistance and reclamation finds a visual echo in Ghana: An African Portrait by Paul Strand. In his images, Ghana’s post-independence essence is not captured through grand monuments or official ceremonies, but through the quiet confidence in the faces of its people – the market women, the schoolchildren, the craftsmen. Each photograph resists the exoticizing gaze often cast on Africa. Instead, Strand’s lens reveals a nation not in search of an identity, but in possession of one – layered, dignified, unyielding.

The portraits read like visual affirmations of Ghana’s postcolonial promise. They reflect not a people broken by colonization, but one rooted in deep continuity and collective memory. The dignity in the eyes of a blacksmith, the composure of a girl in school uniform, the tension in a weaver’s fingers – all serve as metaphors for a nation in the process of reassembling itself, proudly bearing its fractures like Kintsugi gold.

Strand’s Ghana is the visual embodiment of the idea Ghana has always aspired to be: a people who remember who they were before conquest, and who speak back to power—not always with noise, but with presence, with permanence, with pride.

What is Ghana? Ghana is an idea, yes; but one you can see etched in faces, feel in rhythms, and trace in the quiet but firm defiance of a people who insist on being seen whole.

B.

There is an ancient Japanese art form called Kintsugi—the practice of mending broken pottery with lacquer mixed with powdered gold or silver. Rather than disguising the cracks, Kintsugi illuminates them, transforming damage into beauty. It tells a story of survival, of something made more valuable because of its fractures (5).

Ghana, too, is a vessel of many pieces—fragments from early kingdoms and ethnic settlements, each with their own languages, customs, and worldviews. In pre-colonial times, there was no Ghana as we know it (6). The land was a mosaic of independent groups, coexisting and sometimes clashing, until European intervention stitched them into the colonial construct once called the Gold Coast.

Today, Ghana is a tapestry of tribes and tongues – Akan, Mole-Dagbani, Ewe, Ga-Adangbe, Guan – each with rich cultures and deep-rooted pride. This diversity is our strength, but it also reveals our fault lines. Tribal tensions simmer beneath the surface, erupting in online skirmishes, political pandering, and long-standing regional conflicts. Discrimination festers in subtle and overt forms. Insults are hurled, stereotypes are reinforced, and yet we smile.

Ethnic tensions frequently erupt on social media, with various groups vying for dominance and asserting their perceived superiority over others. Politicians often exploit these divisions, stirring tribal sentiments to gain political advantage. In the northern regions of the country, inter-tribal conflicts persist with little resolution, while in the south, tribes engage in verbal attacks and exchange inflammatory, sometimes deeply offensive, remarks. These recurring clashes reflect a broader national struggle with ethnic cohesion and mutual respect.

To the outside world, we are united—a joyful nation of jollof and azonto, of kente and cocoa. But beneath that polished surface, a phantom potter works quietly, mending the cracks with gold-laced lacquer. The nation appears whole, but only because someone is tirelessly reassembling its fractured identity.

What is Ghana? Ghana is a broken clay pot in the hands of a skilled potter—who dares to heal without hiding the breaks.

C.

Ghana stands as a vivid cultural conglomerate – a mosaic of over seventy ethnic groups, each contributing distinct languages, traditions, belief systems, and worldviews to the national fabric. From the Ashanti’s elaborate chieftaincy systems and Adinkra symbolism to the Ewe’s rhythmic drumming traditions and the Fante’s coastal cosmopolitanism, Ghana’s cultural landscape is both intricate and expansive (7). This diversity is not merely a demographic feature; it is a lived reality, reflected in festivals, oral traditions, crafts, cuisine, and indigenous philosophies that coexist within a single geopolitical space (8). The result is a dynamic interplay between unity and plurality, where cultural expressions often overlap yet maintain their rooted uniqueness.

Yet, this multiplicity has also posed profound questions about identity, cohesion, and nationhood. Since independence, Ghana has embarked on an ongoing quest to forge a shared sense of belonging that transcends ethnic divisions without erasing them. National symbols such as the Black Star, the national anthem, and the celebration of Independence Day serve as attempts to cultivate a common narrative (9). However, the challenge lies in crafting a national identity that does not flatten cultural specificity but instead embraces it—one that harmonizes rather than homogenizes. Efforts like the promotion of local languages in media, the National Commission on Culture’s initiatives, and multicultural education curricula reflect attempts to articulate a cultural language that is inclusive, participatory, and reflective of Ghana’s pluralistic soul (10).

In this delicate balancing act, Ghana offers a compelling model for postcolonial nation-building: a space where the past and present are in constant dialogue, and where identity is not fixed but negotiated. The nation's resilience lies in its ability to celebrate cultural distinctiveness while fostering collective citizenship (11). This process is far from complete, but it continues to unfold with every inter-ethnic marriage, every national debate, and every shared cultural celebration that reaffirms the belief that diversity, when anchored in mutual respect and shared aspirations, can be a source of unity rather than division (12).

What is Ghana? Ghana is a conglomerate of diverse cultures and identities, trying to create a new culture that is common to all the other cultures.

PART 2

D.

There is an ancient spirit that lingers in Ghana. It existed long before I was born, and I have felt its presence for as long as I can remember. As a child, whenever I tried to defend myself against an elder’s false accusation, or dared to question the logic of an older person’s belief, this spirit would appear. It would steal my voice—render me silent. Powerless.

This spirit is revered in Ghana. The old honour it with quiet reverence and pass down its traditions like sacred rites. The young recognize it—and resent it. But over time, as youth ripens into age, they too begin to embrace the spirit, offering it their silence and compliance. And so, the cycle continues.

In Ghana, challenging elders or authority figures is not seen as courage—it is considered disrespect. Cultural codes across ethnic lines place a premium on reverence for elders, obedience to authority, and an almost sacred silence in their presence. As a child, I often sat quietly through decisions that shaped my life, knowing better but knowing not to speak. When I did, my words were acknowledged, but rarely acted upon. Eventually, I stopped speaking. Many of us did.

Ghana is a paradox—a nation that bursts with music, colour, and vibrant expression, yet harbours a deep and enduring culture of silence. The rhythms of our drums, the swirl of our dances, the colour of our fabrics—they speak loudly (13). But our words often do not.

This silence has roots. During colonial rule, Ghana—then the Gold Coast—was considered the model colony of British West Africa. Rich in cocoa and gold, with a growing educated class and relatively peaceful governance, it was held up as a success story. But this illusion came at a cost. Dissent was suppressed; voices stilled.

On February 28, 1948, World War II veterans who had served in the Gold Coast Regiment marched peacefully to Christiansborg Castle, demanding the benefits they had been promised. Before they could reach the gates, colonial police opened fire, killing three: Sergeant Adjetey, Corporal Attipoe, and Private Odartey Lamptey (14). Their deaths sent a shockwave through the nation—but also a message: speaking out comes with a price.

Since then, criticism—no matter how measured—has been met with hostility. Media that question government policies are met with vitriol, intimidation, or worse. Detention (15). Defamation. Silence.

And still, the youth try to rise. They gather, protest, raise their voices. Movements like #StopGalamseyNow – calling for an end to illegal mining that has ravaged our land and poisoned our water – are led by brave young Ghanaians. But again, the spirit appears. Protesters are arrested, detained and denied bail for weeks under harsh conditions and silenced (16). The message remains unchanged: speak softly, if at all.

What is Ghana? Ghana is a culture of silence, cloaked in the sounds of a siren. It parades as a voice for the people—but often crushes those who dare to truly speak.

E.

Ghana emerges not only as a nation but as a voice—a linguist of Africa’s collective yearning, echoing through time with a cadence both ancient and urgent. Like the royal linguist (okyeame) who interprets the king’s words with poetry and authority, Ghana has often spoken not just for itself, but for the silenced and the waiting. In 1957, it broke the colonial spell with a voice so resolute that its vibrations crossed oceans and borders, inspiring movements from Harlem to Harare. Its call was not shrill with vengeance but sonorous with possibility: a proclamation that African identity could be proud, sovereign, and whole (Nkrumah, 1961). Ghana's voice, forged in tradition yet fluent in revolution, became the mouthpiece through which others found the language of freedom.

This symbolic stature is mirrored in Paul Strand’s Ghana: An African Portrait, where the visual grammar of ordinary Ghanaians—market women, drummers, blacksmiths, students—forms a quiet but defiant poetry of dignity. Strand's lens captured not a monolith, but a layered soul: one that dances, debates, worships, and builds. His images narrate a nation that is not merely postcolonial but perpetually reimagining itself through the rhythms of its people (17). Through these portraits, Ghana is revealed not as a backdrop to history but as a protagonist, with a face turned towards the future and feet grounded in ancestral rhythm.

Ghana is also a pacesetter; setting trends for others to follow. Professor John Collins, a leading scholar on West African music, traces the roots of highlife music to the late 19th and early 20th centuries in Ghana (then the Gold Coast), describing it as a musical melting pot of African rhythms and European harmonic and instrumental structures. Highlife is not a single genre, but rather an umbrella term that encompasses various sub-styles that evolved over time (18). It is through highlife music that other music genres take their root. Most notably the popular afrobeat that has taken over the musical world today.

To envision Ghana today is to encounter a narrative in motion—where voices from Accra’s bustling streets to Tamale’s courtyards negotiate what it means to belong. It is a place where kente threads, Afrofuturist murals, and protest slogans weave a new linguistic tapestry of pride and purpose. Ghana continues to speak: in literature, in diplomacy, in culture—and others still listen, borrowing its tone, its tenacity, its truth. It is not just a beacon, but the fire itself, kindled again and again by generations determined to speak boldly and live freely.

What is Ghana? Ghana is a beacon of hope – a pacesetter who others are looking up to to set the trend for others to follow.

CONCLUSION

Ghana is, and has always been, more than the sum of its borders or the pages of its constitution. It is an evolving portrait—stitched together by memory, song, struggle, silence, and resistance. It is the cracked pot repaired with gold, not to disguise its damage but to dignify it. It is the voice that dares to whisper when shouting would cost too much, yet still finds ways to be heard—in rhythm, in protest, in music, in metaphor.

Ghana is a paradox and a promise. A land where silence coexists with song, where ancient empires echo through modern identities, and where the future is forever being negotiated between generations. It is the okyeame and the orator, the potter and the vessel, the fire and the flame.

To ask “What is Ghana?” is to pose a question that cannot be fully answered in prose or portrait, but must be felt—in the tension of a drumbeat, in the eyes of Strand’s subjects, in the hushed defiance of a protester’s chant, in the bold humility of a child listening to Nkrumah’s voice.

Ghana is an idea. An inheritance. A living language. A mirror of contradictions, mended not to perfection, but to purpose.

And still, the potter shapes. And still, the nation speaks.

***

About Kofi Dzogbewu

Creative, Thinker, Knowledge Seeker.

Born and raised in Accra, Ghana, but from Avee-Tokor in the Volta Region of Ghana.

Reimagining Ghana means defining my counry from a young Ghanaian’s perspective.

***

References

(1)

Levtzion, N. (1973). Ancient Ghana and Mali. Methuen & Co.

(2)

Conrad, D. C., & Fisher, H. J. (1982). The Songhay Empire and the Mali Empire. In The Cambridge History of Africa (Vol. 3). Cambridge University Press.

(3)

Nkrumah, K. (1961). Africa Must Unite. Heinemann.

(4)

Gyekye, K. (1996). African Cultural Values: An Introduction. Sankofa Publishing Company.

(5)

Kintsugi: The Healing Power of Pottery Repair https://www.gov-online.go.jp/eng/publicity/book/hlj/html/202008/202008_07_en.html#:~:text=Kintsugi%20(literally%2C%20gold%20seams),with%20gold%20or%20silver%20powder

(6)

Exploring the Rich History of Ghana: A Journey Through Time https://www.gvi.co.uk/blog/smb-exploring-the-rich-history-of-ghana-a-journey-through-time

(7)

Gocking, R. (2005). The History of Ghana. Greenwood Press.

(8)

Gyekye, K. (1996). African Cultural Values: An Introduction. Sankofa Publishing Company.

(9)

Nkrumah, K. (1961). Africa Must Unite. Heinemann.

(10)

Yankah, K. (2012). Speaking for the Chief: Okyeame and the Politics of Akan Royal Oratory. Indiana University Press.

(11)

Appiah, K. A. (1992). In My Father's House: Africa in the Philosophy of Culture. Oxford University Press.

(12)

Adjei, M. (2007). “Decolonizing the African Mind: Further Analysis and Strategy.” The Journal of Pan African Studies, 1(10), 85–110.

(13) https://www.motac.gov.gh/dance/#:~:text=These%20dances%20are%20performed%20to,the%20National%20Theather%20of%20Ghana; https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/popular-music/article/ghanaian-highlife-sound-recordings-of-the-1970s-the-legacy-of-francis-kwakye-and-the-ghana-film-studio/CC4AE025388AA3CA6ED5CCEC9C99AB4D

(14)

The Riots of 28th February 1948 http://praad.gov.gh/index.php/the-riots-of-28th-february-1948/#:~:text=Before%20reaching%20the%20castle%20the,Attipoe%20and%20Private%20Odartey%20Lamptey.

(15)

Ghana's culture of silence: Baffour Ankomah https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03064228708534334

(16)

#StopGalamseyNow: 53 anti-illegal mining protesters arrested

https://mfwa.org/issues-in-focus/stopgalamseynow-53-anti-illegal-mining-protesters-arrested

(17)

Strand, P., & McCall, A. (1976). Ghana: An African Portrait. Aperture.

(18)

Collins, John. Highlife Time. Anansesem Press, 1996.